Home > My father and Lewy body dementia – an essay by Jane Sigaloff

As Lewy Body Dementia Awareness Week 2021 gets underway, we are delighted to publish a special essay by Jane Sigaloff. Jane is a published author and in this powerful piece she describes the range of emotions she experienced during her father’s Lewy body dementia journey. Peter was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia in 2015 and died in 2019 at the age of 76. In the essay Jane paints a picture of her father before his illness, and documents the impact that Lewy body dementia had on their whole family.

Jane ends her essay with a call to action – for all of us to spread the word and raise awareness of Lewy body dementia. To support each other and look out for those caring for a loved-one, who may be exhausted and isolated. For more research on the causes of the disease and treatments. All of these are part of the core mission of The Lewy Body Society and Jane reminds us exactly why the charity was founded 15 years ago, and why we continue to raise awareness, campaign and fund research into Lewy body dementia.

An edited version of this essay appeared online and in print edition of the Daily Telegraph.

My father and Lewy body dementia – Jane Sigaloff

There has been a lot of talk of menopause in the media recently, about bringing it out of the shadows, removing the stigma. Mental illness is no longer taboo. Cancer has been out of the closet for a while. Dementia on the other hand is still not really socially acceptable. People don’t know what to say and so they say nothing. It’s the British way.

In 2015 dementia overtook heart disease and stroke as the UK’s biggest cause of death. Annual death statistics for England and Wales show the number of people dying of dementia steadily increasing year on year. Most people have heard of Alzheimer’s Disease but almost nobody has heard of the second most common form: Lewy body dementia (LBD).

My father Peter died in October 2019 after a ten-year battle with Lewy body dementia. Except when you receive this diagnosis there is no actual battle. It is a cul-de-sac of a diagnosis, an inevitable decline to the end, at varying speeds, with myriad symptoms. And in truth, we had lost him three years before he died at the age of 76.

Crudely, Lewy bodies are abnormal clumps of protein that gather inside brain cells. They were first discovered by German Neurologist Dr Friederich Lewy in 1912 and were linked to people who suffered with Parkinson’s disease. In LBD they particularly like to congregate in the areas that are responsible for thought, movement, visual perception, sleep regulation and alertness.

All the layman needs to know is that LBD is the golden ticket of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases rolled into one. With some visual hallucinations and sleep disturbances tossed in as a bonus. I don’t mean to sound irreverent. My dad was (and both his children are) very sarcastic. It’s a family thing. We are hoping that the Lewy bodies are not.

When Robin Williams was finally diagnosed with LBD, having suffered for several years with ever worsening, torturous and confusing symptoms, he decided to exit, stage left, at his own direction in 2014. His widow, Susan Schneider Williams, has written insightfully about his traumatic experience as he felt himself disintegrating. She now serves on the Board of Directors for the American Brain Foundation.

Many of the symptoms come and go for years in the early stages of LBD and can be mild, making diagnoses difficult and often incorrect at first. My father was bewildered by many of symptoms that even he, a career hypochondriac, couldn’t really link together. The doctors were struggling to join the dots too.

With the benefit of hindsight, he was displaying symptoms as early as 2006. He had been increasingly anxious in the years following his retirement and was put on mild anti-depressants. He had shuffled around in his slippers for years, not really picking up his feet and it didn’t occur to us that this, and his occasional stumble, was anything out of the ordinary. He’d always liked a nap and these became longer and more frequent. When he gently reversed in to a friends’ car in his driveway we teased him about getting older. When he clipped the kerb during a couple of local errands in the car, I was concerned. This was a man who had always known the width of this car to the nearest millimetre and had for years enjoyed accelerating through width restrictions.

And then early one morning, he failed to understand that the row of numbers on his clock radio translated to the time. At first I thought he was winding me up. He had no trouble with the clock face on his wristwatch but the 0622 on the digital display meant nothing to him. We tried to laugh it off, to play it down, but the looks on our faces suggested that we both knew things were looking down.

After several false starts, his LBD was finally diagnosed in 2015. The last seven years fell into place as we ticked off almost every symptom on the list. Recurring visual hallucinations – in his case actual other people in the room, sometimes in dark corners, others just in front of him, generally friendly folk or people he knew. Restless and disturbed sleep. Slowed movements. Shuffling. Difficulty in walking. Reduced motor function. Drowsiness. Lethargy. Staring blankly. Reduced communication – he had started to avoid using the phone as he could no longer find the correct words in real time. Lack of motor control – by now he was struggling to use a pen or a knife and fork. He could no longer read.

Like Alzheimer’s disease, LBD is progressive and there is no set time scale. Some people have two years, others have twenty. The average is 5-8 years. There is no treatment and no cure.

If Lewy Body Dementia Awareness Week can help to raise the profile of LBD and provide more information for sufferers and their families, as well as acknowledging the huge burden of care, perhaps these people will finally feel heard and supported. Many dementia patients have to suffer in silence or confused conversation but those who care for them and their families shouldn’t have to.

My Dad had a year, post diagnosis, when the progression was slow. For these precious months, he was mostly present and indeed intermittently good company when he was awake. We started to relax slightly. Maybe it wouldn’t be as bad as we had imagined.

Things suddenly changed over the course of a week in March 2016. He developed an acute urinary tract infection and needed a stay in hospital. He returned home no longer able to walk or talk, needing a wheelchair, a commode, a hoist and round the clock care. For the next three years I have no idea how he was feeling, or how aware he was of his decline as he could no longer tell me. He was silenced. I had to guess.

The last two-way conversation we had was just after his 73rd birthday. While some men are known for being monosyllabic, this man loved a chat. Indeed I used to clean my entire flat whilst he was on the other end of the phone, just calling for a quick catch up and regaling me with the minutiae of his week. He’d spent forty years as a dentist, distracting his patients with small talk, making people chuckle at times when they had thought they would be scared. Over the next few years I tried to return that favour. I continued to chat to him, to sing to him, to hum along to our favourite music in his presence, made him playlists and hoped against all the odds that there would be one moment when he would join in, harmonise or interrupt me. The silence was deafening.

He had always liked to talk things through. I vividly remember a conversation that we had when, a few years earlier, Alzheimer’s disease had been suggested as a diagnosis. He was lying on his bed in his bathrobe, just having a little rest after breakfast before getting dressed for the day. He was worrying about all sorts of things. “What if I can’t speak?” he had asked me. We joked around for a bit. “You may not remember who you are, what you said or who you said it to but why wouldn’t you be able to speak? That’s not a dementia thing”, I countered. And then his greatest fear was realised and looking back on it, it was as if somehow he knew it was coming.

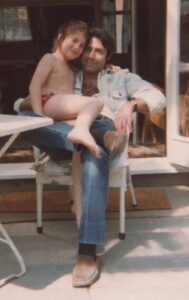

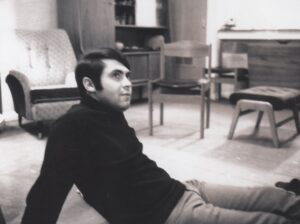

My father would have been the first to admit that he was not a perfect man. He was a gentle soul, he was funny, he was patient, he was kind. He loved a glass of red wine, a menthol cigarette, a Kit Kat for breakfast, lying in the sun and a beautiful and intelligent woman. He married two of them over the years and had relationships with many more. He loved music, comedy and for his entire life, farts made him laugh out loud. He was quite possibly the last subscriber of Car magazine, he loved The Muppets, Snoopy, Inspector Clouseau, Blackadder, black roll neck jumpers and faded Levi’s denim jackets. He loved his family. He had charm in abundance and not a confrontational bone in his body. Everyone loved him back.

Now, a few years down the line, I do my best to remember him this way. As the man he was before, instead of the shell that he became. And before he moved into his shell, there were moments of terror, for him and for us. When he still had the strength to stand but no longer the ability to walk, there were falls. There were months of momentary bouts of uncharacteristic anger, of stubborn determination. Lashing out in frustration. Unable to marshal his limbs at times, an iron grip that I’m not sure he could fully control. Angry outbursts, spitting out food, moments of rage. Perhaps trying to control the only things he could at that stage? Again, we were only guessing. It was all that we could do. My stepmother Margot cared for him with unending devotion and patience. There were times when looking after him nearly broke her and yet she rarely complained.

When the final physical storms passed, the now silent shell remained. If you didn’t look him in the now more vacant eye, the exterior was familiar. I sat with his hand in mine for many hours. Committing his fingers to memory. He was alive but not present. There but not. For some time non-verbal communication was possible. His eyes spoke ten or twenty words but gradually these faded too.

In the last couple of years his eyes were often closed. I always hoped that he was watching re-runs of his finest moments on the inside of his eyelids rather than hiding from his living nightmare. He was mainly calm. Had he made his peace? Did he know what was happening. Or was he silently furious. Could he comfort himself with old memories? Could he access them? What did he know?

Margot continued to care for him night and day. She nursed him, often emotionally shredded, as she watched the love of her life disappear in front of her eyes, from the inside out. A cruel and slow unpicking of self.

He had two periods of residential care. When he could no longer walk, my stepmother needed to move them into a bungalow so as to be able to continue to look after him at home. The second time, she needed back surgery having almost worn herself out in her attempts to give him the best possible care.

She had an electric hoist to help but he was by this stage an 11 stone pet/baby/husband. He needed toileting, feeding and washing. He couldn’t drink unless you held a plastic cup to his lips. Sometimes he would sit with the sip in his mouth for many minutes, forgetting that he had to swallow. He had a mattress that turned him during the night to prevent him getting sores. When he was in a home that wasn’t hers, she visited him every single day. He was one of the fortunate ones.

Care homes are a strange beast. There is unquestionably room for improvement, for greater provision, for fairer provision, access for those without funds and indeed a need for far more care-home beds. In the current system, overworked, underpaid staff (the majority of whom have hearts of gold) look after other people’s relatives as if they were their own.

These are artificial communities. My dad was kept in a locked wing. He could no longer walk, but some of his fellow residents (his well self might have jokily referred to them as inmates) were keen to leave the building. Many were very vocal, some distressed. You didn’t really know what you would encounter from one day to the next. The certainties were stuffy day lounges, a faint smell of pee or bleach or both, mumbling television programmes – usually Heartbeat or Morse – music from the 1950s and the 1960s on a loop and then, alarms. Constant bleeping in the background – calling care staff to residents’ rooms, to toilets. There was no peace.

At this stage my father was in Norfolk and I was in London. It was a six hour round trip and I drove up for the day, straight after dropping my children at school, every few weeks. We visited as a family at half term and in school holidays. My girls saw him at home and in the home. They played in his wheelchair. They took it all in their stride, as children usually do if you give them the chance. My daughters will never remember the fun, caring and irreverent man he once was. To them he was just a man in a chair that looked a bit like me. But they loved him, because I did. We often spoke and still speak about the good times. I don’t want to lose my memories.

I never knew if he had any concept of the time between our visits. I hoped not, guilty that I couldn’t pop in more often. Sometimes there was a smile, a kiss and definite recognition. On the days his eyes were blank I had to dig deeper, but I felt that he knew we had a trusted connection.

Once he could no longer speak to me on the phone, or in person, he was the last person I thought of before going to sleep and the first person I thought of when I woke up in the morning. In a world when you can send a text message across the world in an instant, I liked to think I could beam him one, brain to brain, via some father-daughter virtual expressway. It helped me, day to day.

The only Christmas that he spent in residential care, I brought my children to visit him in mid December. We were in Santa hats and Christmas jumpers and after three hours of singing along to festive tunes in the car, we were in high spirits and had almost forgotten that we weren’t visiting the father of my youth. Now, the odd word was uttered enthusiastically but more often or not it was not the correct one. He burbled sometimes, the intonation of a sentence there, imitating conversation like a toddler.

He was in his usual chair when we arrived – he couldn’t leave it without assistance – and we bounded over full of jingle bell love and festive cheer, brandishing his favourite treat – a chocolate cream éclair. He looked at us. Blankly. Then at the small wrapped gifts we had placed on his tray table. Suddenly he was sobbing. Tears were rolling down his cheeks, snot dripping from his nose. His shoulders heaving. We hugged him and kissed him and wiped his nose. He remained inconsolable. I called my step-mum and asked her to come and get the girls. And then I sat with him quietly. I felt guilt. Perhaps we had reminded him of the joy he could no longer partake in. Eventually I went to make us a cup of tea and when I returned he was asleep, no doubt exhausted by his outburst. When he next opened his eyes two hours later, he was back to his usual-for-now self. No visible anguish. A smile for me and a puckering of his lips. The chocolate éclair disappeared in three mouthfuls.

One of the nurses told me that extreme outbursts of emotion just happened sometimes. And that it was probably just a coincidence. I wasn’t so sure. After that visit, I vowed to write him a letter and read it to him when I next sat beside him. I wanted to tell him that I loved him, that I was in awe of his bravery and his calm. Instead after my long drive to get there, I ended up talking about the traffic and the weather.

For the last 18 months, he didn’t recognise me any more. My heart broke a little. I started to grieve while I was sitting next to him. The twinkle in his eye finally deserted him around 6 months before he died. But he hadn’t really been with us for many years. He was still alive when Brexit happened, when Aretha Franklin died, when his sister died – and yet he was unaware, blissfully so – it was the only silver lining.

He was only 76 when he died. In many ways it was a relief and release, undoubtedly for him, but for us too. In his final days we hugged him and kissed him and held his hand. We played him his favourite music. We gave him our permission to leave. He was surrounded by love. It helped us. But whether or not if helped him we will never know. It would be lovely to think he is wafting around somewhere in a fluffy white bathrobe, holding a tepid mug full of filter coffee, whistling the harmonies to his favourite ELO tracks.

The end was nothing like a Hollywood movie. For a start it lasted for nearly two weeks. I said goodbye only to find myself back in the car on the A11 on my way for a repeat performance a day or two later. There were several curtain calls. One day, I lay alongside him on his bed for several hours, just listening to him breathing, feeling the skin of my arm alongside his and absorbing as much of him as I could.

His heart was so strong that it continued to beat for 13 days and nights after he had last swallowed food or water. He was on a morphine driver that was adjusted, in miniscule increments, by the District Nurse who visited every day or two. When we weren’t crying, we teased him that after decades of doing very little physical activity, when napping was his endurance sport of choice, that this was his Marathon Des Sables. His final hurrah. We had to laugh. Had to.

There was nothing we could do but wait and wonder. It is, of course, never ok for one human being to take another’s life but yet you wouldn’t allow the family pet to suffer for this long. As a family we had decided not to put him on a drip. He might have lasted a few more months with one. But this felt like it was the least that we could do. When, during this final stretch, my eight year old daughter asked me, on the 430 bus en route to school, how we knew that Grandpoo wasn’t thirsty, I had to gloss over the truth.

At no point could I have ended his life for him, but I can’t help thinking that had he been able to request one for the road, he would have seized the opportunity to leave us all a few years earlier. The Campaign for Dignity in Dying suggest that 44% of people would break the law as it currently stands and help a loved one to die, risking 14 years in prison. When death is inevitable, should suffering have to be? We must continue to discuss Assisted Dying. It is undoubtedly an emotive and ethical minefield, a difficult dialogue for doctors and patients, and not a conversation my father was physically able to have in his final years, let alone his final weeks. This inability for many patients to provide final consent, I suspect, will prove to be the biggest stumbling block.

My stepmother cared for my father around the clock with such love and tenderness that the rest of us could live our lives between visits without becoming consumed with guilt and for this I will always be grateful. And for the fact that he died before Covid arrived.

Who knows what, if anything, happens after death? When I was asked as a 9 year old if I believed anything came after death, I was as definite as child can be. Yes. A Funeral.

He had one of those and his ashes are now in The Thames near Chiswick Bridge, a few hundred metres from where he grew up. I have to hope that he didn’t suffer during all those years, that somehow his brain took him somewhere nicer and that the calm and bravery he displayed over the months was the same inside and out.

Joe Biden wrote, some time after the death of his beloved son Beau, ‘There will come a time when the memory of a loved one brings a smile to your lips before it brings a tear to your eye.’ I was able to do most of my grieving whilst he was still alive. I missed him the most when I was with him.

This week is Lewy Body Dementia Awareness Week. Ultimately it is only the friends and families of those with LBD who can take action, who can spread the word and who can support each other.

In 2020 we rediscovered the value and importance of our communities – be they friends, neighbours, schools or families.

Thanks to technology these communities don’t need to be local in their geography. So many of those caring for people with dementia are isolated and exhausted.

Let them lean on those of us who have already been down this rocky road, knowing they are one in a million for the job that they are doing but also one of millions of family members and carers who have been through the same situation and survived to tell the tale. Survived to live again. When they are ready to, let them talk. We will listen.

More research into LBD is needed. Is there a genetic predisposition or are environmental factors a cause? Are there triggers? What, if anything, can we do to keep it at bay? Its victims cannot hold a conversation let alone start a new one. The onus is on their families and friends. We don’t want to let them down.

Jane Sigaloff

To receive regular news updates, resources, events and breakthroughs in the fight against Lewy body dementia please enter your email address….

We will only contact you in relation to latest news & updates that we think will be of interest to you. We will not disclose your information to any third party and you can unsubscribe from our database at any time.

© 2023 The Lewy body Society. Registered Charity No: 1114579 (England and Wales) and SC047044 (Scotland). Website by ATTAIN